I been working or a book about Marvel’s Earth 616. The working title is

I been working or a book about Marvel’s Earth 616. The working title is

The Secret Origin of Marvel’s Earth-616 (the Marvel Cinematic Universe) or Alternate Universes and Why To Make Them.

You can buy it here.

Here is the idea and the opening extract:

Summary

The Marvel universe is one of most successful cultural phenomena of recent times. Marvel Studios produces films that consistently outgross most others. Marvel’s stories and pantheon of characters exist within a ‘multiverse’ consisting of multiple universes, and the principal one is called Earth-616. Most of the films, TV series and comic books take place within this version of the universe.

The universe was created by David Thorpe when he was writing Captain Britain in the early 1980s while editing comics for Marvel UK. Originally intended as an alternative universe, it subsequently became the main one for Marvel’s stories.

This is his story of its origin and meaning, and discussion of his other comics projects. In the process David discusses how he came to work for Marvel and what it was like, the golden comics scene in Britain in the 1980s when Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison and Alan Moore rose to fame, the importance of alternate realities and secret identities, the reasons for the appeal and success of Marvel superheroes and the Marvel universe, and relates fascinating anecdotes about Marvel and other comics creators and top literary authors of graphic novels he subsequently commissioned and edited.

Foreword

Just over 30 minutes into the movie Spider-Man: Far From Home, Mysterio tells Spider-Man that we live in a multiverse. “This is Earth dimension 616. I’m from Earth 833.”

Hoo boy, as Stan Lee used to say. I got a thrill when I heard this. Because I invented Earth 616, which is where most of Marvel’s films and stories are set.

Sheesh. For, at the time of writing, the total worldwide box office revenue for Marvel Cinematic Universe films is US$ 22.56bn, four times more than DC Comics’ superhero films. It’s the most successful film franchise of all time.

There’s a story on the Internet that I don’t like superheroes. Nothing could be further from the truth. They’re aspirational. They’re inspirational. And these days you can’t get away from them.

As a child I decided I wanted to work for Marvel Comics one day. And would you believe it, I did – in the early ’80s, in the London Bullpen, although I was more like a lamb than a bull and we didn’t use pens, they were so old school, we had a modern golfball typesetter. I edited comics and penned a few tales about Captain Britain. I invented a few crazy characters that, in the Marvel way, took on a life of their own.

And an alternate universe. And the concept of the Marvel multiverse.

How was anybody to know at the time that by this universe, Earth 616, despite the best intentions of its creators, would go on to become the main Marvel universe, in which most of its stories take place. And many other universes within the multiverse have since mushroomed and continue to do so.

This book tells how that universe – and the idea of alternate universes within Marvel – came to be – because of the crucial role of Marvel Comics and superheroes in my life. Think that’s sad? Read on.

‘Cause along the way I reflect on why so many people love superheroes, and on the vital importance of alternate universes and secret identities to me – and perhaps to you, even if you don’t know it.

I also reveal some other interesting stories about the inspiration for Earth-616, the origin of Neil Gaiman and Alan Moore and more about the rest of my involvement with literature and comics.

If it changed my life for the better it might change yours. I hope so.

Preface

Everyone needs at least one universe to escape to, as long as there’s a way back.

A universe in which you can be yourself.

Discover who you are.

Find treasures.

And emerge into the mainstream universe more whole than when you left, bearing gifts – for yourself and for others – gifts that enrich your life and work.

A universe isn’t necessarily another place.

It might be another way of looking at the same universe.

It might be a secret universe inside yourself.

Or it might be the same universe with something very subtly changed.

And that thing could be you…

Why Marvel has universes!

I didn’t set out to create the Marvel universe, of course, and no one was more surprised than I to discover that I had. No one person could do that anyway. It’s in the nature of the beast that Stan Lee and his rogue’s gallery of artists brought to life, like winding up an immense clockwork machine that it is a collective endeavour, the product of many creatives who together make up a hive mind.

It evolves over the decades by a kind of unnatural selection that ensures its ongoing survival and adaptation to changing tastes and markets. It’s like a massive instance of that surrealist game, Le Cadavre Exquis, or The Exquisite Corpse, where successive players complete a story with disregard for what went before, a notion that appeals to the surrealist in me immensely.

So the Thor of today bears only passing resemblance to the Thor of the early nineteen sixties. Each age gets the heroes it needs and deserves. And the Earth 616 of today is not the same as the one I dreamed up. But the concept of alternative Earths is the same, and, though many, they are finite and connected. Marvel needed this concept to resolve a number of paradoxes and questions concerning the relationship between its version of Earth and ours, not to mention, when the movies started being churned out, between the version in some of the comics and others, and the one in the movies, each of which are necessarily self-consistent but mutually inconsistent, if that makes sense.

Earth 616 was a convenient pre-existing universe to serve this purpose. No matter that our intention in creating it had been almost the opposite: to create a version of Earth separate from the rest of the Marvel universe where we could do what we liked. The Marvel way is nothing if not pragmatic. So I didn’t mind when I discovered this is what had become of my baby.

On the contrary how could I help but feel immense pride that the small seed I planted in the garden of Marvel’s past beginning with the Captain Britain story in Marvel Super Heroes #377, September, 1981, has borne such strange fruit. It’s provided a rich ecosystem to support amazing entertainment. It provides another example of one of my mottos in life, which is: you never know – you can never tell what will happen when you put things out there. It could have vanished without trace. But it didn’t, proof of another belief, that you can’t keep a good idea down.

So if you enjoy the Marvel cinematic universe as much as I do, making seem real all those epic escapades that boggled my brain as a youngster, providing hours of escape from dull everyday life (the real reason why I like and why I’m sure you like superheroes), also be grateful that these cosmic battles and wanton destruction don’t occur in our universe and that Thanos isn’t going to be an uninvited guest at your birthday party.

This book tells why.

What is Earth 616?

Marvel Comics is 60 years old. For the first 25 to 30 years there was just one Marvel universe, and it was nameless. With the exception of non-superhero characters (like Millie the Model and Rawhide Kid) and characters linked to franchises (Transformers, Star Wars), all of Marvel’s stories were meant to build into a consistent meta-novel, hundreds of thousands of four-colour pages in length.

The amazing Spider-Man, invincible Iron Man, fabulous Fantastic Four, uncanny X-Men, incredible Hulk, Doctor Strange, the Avengers, the Silver Surfer, Captain America, the mighty Thor. Just to utter these names is to conjure worlds of associations for fans! From the time of the publication of the first Fantastic Four in November 1961 and the first Spider-Man tale in Amazing Fantasy 15 in August 1962, the characters and their adventures proliferated, expanding exponentially over the years in an intricately connected web of fantabulous interdependent developments.

From the start, Rule One of Marvel was that writers and readers were meant to know everything that had gone before. Writers would build on the first few years’ foundations laid by writer/editor Stan Lee and artists Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and Don Heck, an increasingly massive and complex superstructure, a towering edifice housing thousands of corridors, stairways and rooms, each containing a story, an event, a character. Editors’ footnotes often explained these internal references and cross-references. It was meticulous, miraculous and maze-like.

Woe betide writers and editors sometimes accidentally overlooking a past incident, or contradicting one, for they would suffer a deluge of letters from fans notorious for possessing the memories of elephants. (“In Human Torch #3 Xemu was called Zemu.” ) Anyone pointing out such a genuine and significant mistake would be rewarded with a no-prize, but editors would frequently contrive creative reasons to explain away these apparent anomalies.

To start with, when everything was written and drawn by a small team, Rule One made sense. This was when Marvel was owned by publishing company Magazine Management run by Martin Goodman, publishing besides superhero comics, pulps, “girlie” magazines, Hollywood scandal rags, true crime, horror, western, humour, paperback books, and comics. The Marvel Bullpen that Stan hyped in the letter columns and editorial pages in early Marvel comics probably had no more members than the fingers of your hand. In the early days of Fantastic Four and Spider-Man, Stan Lee was crammed in a cubbyhole of an office with Flo Steinberg, a part-time Sol Brodsky, and the occasional production artist. The artists, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko and so on, were freelancers who would pop in to drop off their work in exchange for a cheque from Flo. No one had time for error-checking.

Besides, a self-consistent universe was a great way to sell more comics – you had to read them all to get the full picture. Cross-title continuity and guest-starring of one lead hero in another’s title were encouraged (the appearance of Spider-Man always improved sales). As more writers and artists were drawn into Marvel’s gravitational orbit, and the number of titles proliferated, the superstructure became more and more unwieldy, in line with the Law of Increasing Complexity which states that simplicity never lasts, just as entropy – disorder – always increases.

So mistakes were frequent, and spotted by letter writers. The best ones were Spider-Man being called Peter Palmer (in his second story), Hulk being David Banner, and Mister Fantastic’s hands often being drawn left-for-right by Kirby (not difficult to get wrong when his arms stretched and tangled so far!). Ever one to turn a problem into an opportunity, Stan made up the “No-Prize” in 1964 to reward spotters, but only if they could provide a plausible reason why it wasn’t really a mistake. It was a joke — there was no actual prize/award – but many readers didn’t get it, so after three years a real no-prize was invented in the form of an empty envelope bearing the message “Congratulations, this envelope contains a genuine Marvel Comics No-Prize which you have just won!”. Needless to say, some still wrote back wondering whether Marvel had inadvertently forgotten to put their “prize” in the envelope.

Under editor Paul Neary’s direction I created Earth 616 as a way of avoiding such contradictions. Taking over Captain Britain from me, Alan Moore continued this innovation.

I didn’t just create one alternate Earth, but almost an infinity of them: the concept of a Marvel multiverse, which was straddled and steered by the sublime Saturnyne and her faithful Avant Guard team. Once the multiverse’s existence came to the attention of the New York bullpen, they began to realise their own possibilities for it. Writers who came up with fabulous storylines for characters that couldn’t be published because they’d break Rule One of Marvel now had a way out: situate them in an alternate universe! The Ultimates are a foremost example.

There was one critical factor in why Earth 616 became the opposite of what we intended by its creation, i.e., the main Marvel universe: we did not tell the New York bullpen why we invented it. I just guess that they assumed our stories actually happened in the same universe as theirs – because their, original, universe, crucially did not yet have a number. Neither did I, or Marvel UK editor Paul Neary, or Alan Moore ever give it one – the square root of minus one for example. If we had, things would be different. Earth square root of minus one would have been the main Marvel Universe and 616 would have remained a minor dimension, perhaps a dumpbin for weirdo British superheroes.

Artist Alan Davies encouraged writer Chris Claremont, when he took over writing the character again on Excalibur to explicitly state this assumption that “our stories inhabited the same universe”, and this is how Earth 616 became the principal reality for the majority of Marvel’s superhero tales.

That’s the power of naming.

Not that editors in the NY Bullpen necessarily went along with this. Several are on record as saying that they never use the term Earth 616, and they would like it to die out. But nobody has told Marvel Studios. They continue churning out movies – 23 so far at the time of writing grossing over $22.5 billion – set in this dimension. And no one has told Disney, who own Marvel since 2018, hence the excellent documentary series on its streaming channel, Marvel 616.

Some people have become totally pedantic about this. These fans and creators hold to the tenet that Earth 1218 is our reality, where superheroes and other super-powered beings don’t exist, and we read Earth 616 comics while watching movies set in Earth 199999.

They argue that the movies can’t exist in the same reality as the comics because things happen differently, such as Hank Pym made Ultron in The Avengers comic book, not Tony Stark as in the movie. Both The Silver Surfer and Adam Warlock were big players in the Infinity War comics but they are absent from the movie. And Black Widow and Hawkeye were definitely not founder members of the Avengers in the comic book, as they are in the movie.

But so what? In Spider-Man: Far From Home, Aunt May is relatively young and fit, while in the original comics she is grey-haired and frail, Ned Leeds didn’t exist, and MJ was a red-head. Peter Parker didn’t tell anyone he’s Spider-Man in the ‘sixties, but in the movie this secret is known to a select few. Who cares? It’s explicitly set in Earth 616 and follows on from the Avengers movie quartet storyline, ergo they’re in 616 too.

The same myths and legends from cultures as diverse as India and Greece have been told scores of times in a multitude of interpretations. Those vivid tales of Karna or Krishna from the Mahabharata have been adapted for screen and stage over and over. Compare Ovid’s version of Orpheus and Eurydice to Jean Cocteau’s film Orphée, or Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex to Pasolini’s movie. There are scores of variations and differences but the stories’ hearts are identical. That there are differences doesn’t signify that they take place in another universe.

This is the purpose of a legend or myth: they are open to reinterpretation by successive generations, as long as they remain faithful to the essential truth they carry, to the personalities of their characters and to their themes. We love to see or hear familiar stories retold again and again but with changing emphases.

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were insistent that their stories had a similar status – that they were the modern era’s equivalent of Greek, Norse and Roman pantheons. Perhaps they are. Whether it’s Batman versus the Joker (so what that it’s DC?), X-Men versus Magneto, or The Hulk versus his alter ego; or whether it’s Ariadne and Theseus versus the Minotaur, Icarus and the power of flight, or Prometheus and the theft of fire from Olympus leading to his punishment and Pandora’s box, we never tire of them. Because these tales, like that of Earth’s heroes versus the death-god Thanos, and his love for Gamora, tell us profound truths about human existence.

So of course the Marvel cinematic universe is identical to the mainstream comics’.

But what do you think? I think alternative universes are a different order of meaning. They’re not reinterpretations of similar storylines, they’re different ecosystems, different ‘what ifs’. It’s like the difference between two arrangements of the same song and two totally different songs. Listen to Joe Cocker’s With A Little Help From My Friends, compared to the Beatles’ original, or Paul Anka’s My Way as sung by Frank Sinatra and Sid Vicious. Both wildly unlike each other but recognisably the same chord progressions, words, melody. Bob Dylan and many rap artists even frequently change the words during performances, but, as they say, the song remains the same.

When Alice went through the looking glass, she entered a parallel world and met the Red and White Queens, who didn’t exist in her world. When Captain Britain entered a parallel world he met Captain UK. There’s the difference in a sentence.

The authors of the title Deadpool had meta-fun with this concept of multiple realities, and the notion that we, the comics readers and creators, live in a different universe from the comics. Borrowing ideas from Laurence Sterne’s satirical eighteenth century novel Tristram Shandy and Irish writer Flann O’Brien’s At Swim Two Birds, they sent the eponymous anti-hero to our reality, now numbered by Marvel as 1218, to kill themselves, but Deadpool failed because by definition he can’t appear in a reality with no superheroes and instead he created yet another alternative universe.

At this point these lines from the Tao te Ching, one of the most ancient and profound books on our Earth, come to mind:

The name that can be named is not the real name.

The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth.

The named is the mother of ten thousand things.

Let me paraphrase:

The name that can be named is not the real name.

The nameless is the beginning of our universe.

The named is the mother of ten thousand universes.

The bottom line is that stories set in Earth 616 – not to mention other universes – are proliferating (in line with the aforementioned law) and super-successful. Marvel’s films and tv series, from Thor to Black Panther and Spider-Man, consistently rank high in ratings and box office. It’s bigger than the James Bond franchise. Marvel has become like Apple – a global giant and brand worth billions. Steve Jobs was Stan Lee – the front-man and the face of the intellectual property he championed and the company he led. I’ll analyse this success later.

It was certainly nothing like that when I was employed by them. Those were the wilderness years, when it kind of lost its way, unable to perceive the value it held. It was subsequently owned by make-up company Revlon for a while, who spectacularly messed up. For the Babani Brothers, who ten years earlier held the UK licence and owned the British bullpen, we might as well have been pushing out stories about teddy bears; they didn’t care as long as they could cream off a little profit and own a Rolls Royce.

In that wilderness we were able to plant a seed, one which would grow, like Jack’s beanstalk, into a mighty Yggdrasil, the Norse World Tree, encompassing the world and inhabited by giants.

This book is the story of that seed.

It is with great sadness that we announce the death of the author and environmentalist David Thorpe. He died peacefully in his sleep early on Thursday 25th April in Barcelona.

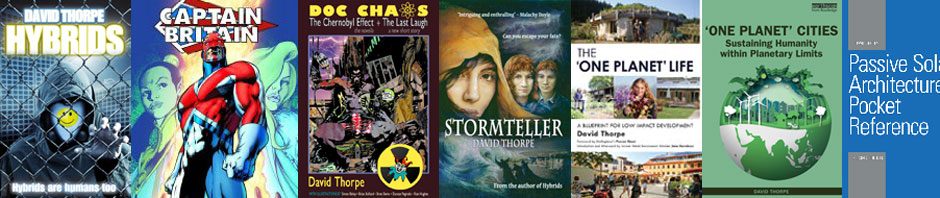

It is with great sadness that we announce the death of the author and environmentalist David Thorpe. He died peacefully in his sleep early on Thursday 25th April in Barcelona. David also continued to write fiction, ranging from screenplays to short stories and novels, including acclaimed eco-thrillers Stormteller and Hybrids. One of his later projects was a rap musical called Validation, produced by the New Works Playhouse, and inspired by his experience of coming to terms with his disability.

David also continued to write fiction, ranging from screenplays to short stories and novels, including acclaimed eco-thrillers Stormteller and Hybrids. One of his later projects was a rap musical called Validation, produced by the New Works Playhouse, and inspired by his experience of coming to terms with his disability. It was only a few weeks after suffering a serious stroke that, against all odds, in his wheelchair, David travelled to Glasgow to launch the One Planet Standard at COP26. Shortly afterwards, Swansea Council led the way as the first organisation to be accredited as a One Planet Standard organisation.

It was only a few weeks after suffering a serious stroke that, against all odds, in his wheelchair, David travelled to Glasgow to launch the One Planet Standard at COP26. Shortly afterwards, Swansea Council led the way as the first organisation to be accredited as a One Planet Standard organisation.

Follow

Follow

I been working or a book about Marvel’s Earth 616. The working title is

I been working or a book about Marvel’s Earth 616. The working title is